Legionella Control

Section 1

Please help to expand this page. |

Section 2

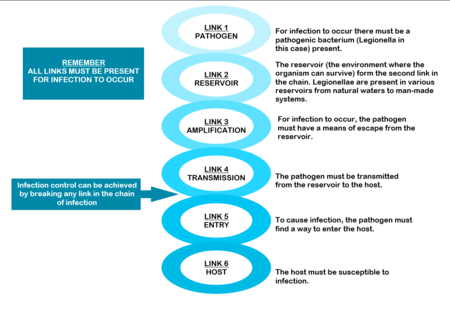

THE CHAIN OF INFECTION

The mere presence of legionellae in a water distribution system does not necessarily imply a human health risk. For human infection to occur, certain conditions are necessary. These conditions are referred to as the “chain of infection” consisting of six links. All the links have to be present for disease to occur (Diagram: Chain of infection ). The first link, the pathogen, was discussed in Section 1.

SOURCES AND RESERVOIRS

Legionellae are natural inhabitants of water, found a wide range of habitats. They are ubiquitous in streams, lakes and rivers. They also survive in dust, soil and mud. In fact, one of the species, Legionella longbeacheae, is so often isolated from potting soil in Australia that soil has been suggested as the natural habitat of this particular species.[1]

Legionellae from these natural environments can be transmitted to man-made water systems by various means. For example, from raw water, during water treatment, as part of post-treatment after-growths within water distribution systems, during building and construction activities and during plumbing repair.[2]

Once established, they can persist in the water supply for long periods of time and are difficult to eradicate. Therefore, their presence must be considered in all aspects of the design, operation and maintenance of buildings. For this to be effective, cooperation between engineers, occupational health practitioners and microbiologists is essential.

Figure 2.3 Man-made sources of Legionella

Water sources that provide optimal conditions for Legionella growth can be separated into those containing “non-potable” and those that contain “potable” water. Non-potable water distribution systems

Heat rejection devices like cooling towers, evaporative condensers and HVAC (heating, ventilation and air-conditioning) systems are often implicated as sources of legionellosis. They contain reservoirs filled with warm, recirculating water that makes them ideal for the growth, amplification and dissemination of micro organisms (including Legionella). In a typical water-cooled system air in induced through or blown over, packing material down which water, circulating from a pond under the packing, is allowed to fall by gravity, producing a large wetted surface that cools the falling water.

The constant fall of water through the tower, the large area of the basin, fill, pipes and heat exchanger, the warm temperature of the water, the high relative humidity and high organic content within these devices provide conditions that favour contamination by algae, protozoa, fungi and bacteria. The risk is increased further by the open nature of the systems, excessive aeration and the constant addition of fresh water to make up for water lost through evaporation.

In systems that are not regularly cleaned, sludge accumulates in the reservoir and slime adheres to water covered surfaces, resulting in the presence of large concentrations of micro-organisms, including legionellae, on these surfaces. In addition, water temperatures below 60°C, the age and configuration of the system, the pH of the water and the presence of certain metals may also increase the risk of contamination.

Water derived from municipal supplies but subsequently stored in cisterns, or conditioned prior to heating, is considered non-potable due to the deterioration in chemical and bacteriological quality during storage. Colonisation of such non-potable sources inside large buildings, such as hotels, factories or hospitals, may be a major cause of legionellosis.[3][4][5]

Potable (domestic) water distribution systems

Legionellae are often present in potable water supplies, especially in the hot water sections of these systems. The organisms may enter potable water supplies from the main source, even from municipal water, and survive standard treatment protocols because most municipal water systems are not routinely screened for the presence of legionellae and the organisms are chlorine tolerant. Once inside the system, they find a suitable environment to multiply and are usually very difficult to eradicate.

Legionella levels can rise from very low to very high within short periods of time. The factors that give rise to these fluctuations are not well understood and often very hard to determine. These factors include the age and configuration of the pipes, the degree of scaling and sediment and the potential for biofilm formation within the system increase the risk of contamination. Water temperatures of 25 – 42°C, stagnation and the presence of certain free-living amoebae capable of supporting the intracellular growth of legionellae are often mentioned as amplifying factors in published reports. The biofilm and scale that form on surfaces in water distribution systems provide nutrients for legionellae and protect them from hot water and disinfectants. Some materials used in these systems, for example neoprene washers, are more readily colonised than others (See Table). Building location may also play a role in the colonisation of potable water with legionellae.

Hot water tanks are often colonised with legionellae, especially at the bottom where a warm zone may develop and scale and sediment accumulate.[6] Hot water piping, especially dead-legs, presents an additional risk as legionellae thrive in stagnant water.

Soil

Outdoors, the soil may be contaminated through contact with Legionella-polluted water and become a source of airborne bacteria during earth moving operations, such as construction work.

|

Very good |

Copper |

|

Good |

Other synthetic materials |

|

Reasonable |

Steel |

|

Not recommended |

Rubber Plastics |

Amplification

Legionellae are usually present in low numbers in natural sources. However, certain factors present in man-made reservoirs can promote Legionella growth and amplification. To improve our understanding of Legionella, its potential to cause disease and how to better control the organisms in water systems, we must understand these conditions. The most important factors amplifying Legionella numbers in man-made reservoirs are listed in the table Amplifying factors for Legionella in man-made sources and reservoirs.

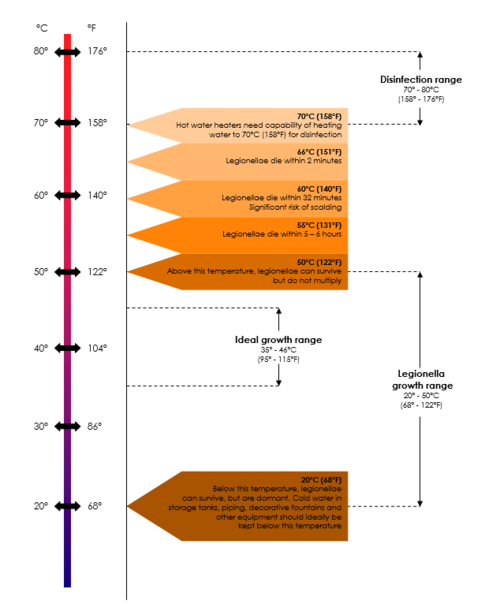

Remember Temperature data is usually based on laboratory studies and is not from actual system (piping) studies, which makes it even less reliable to use for Legionella control. System temperature on its own should therefore not be relied upon for Legionella control, because the so-called “system temperature” rarely indicates one uniform temperature throughout the entire system. Therefore, maintaining the system temperature does not guarantee Legionella control. Also, in plumbing systems, especially larger and/or more complex piping systems, legionellae have been shown to survive at even higher temperatures due to biofilm, dead-legs, and other complexities. It has been suggested that potable water systems be operated at temperatures as high as possible but take into account the risk of scalding injuries and energy conservation requirements.

|

TEMPERATURE |

|

|

pH |

|

|

STAGNATION |

|

|

WATER TREATMENT |

|

|

DISINFECTANTS |

|

|

CHEMICAL PARAMETERS |

|

|

RELATIVE HUMIDITY |

|

|

SLIME, ALGAE AND PROTOZOA |

|

|

CORROSION PRODUCTS |

|

|

CONSTRUCTION |

It is believed that legionellae are released from the soil during excavations from where they can enter the cooling tower of the building, air intakes or water pipes, or may be inhaled directly. Another possibility is that, during construction, nutrients already present in dust and dirt may become more readily available for the organisms. In new buildings, plumbing should be flushed before use. Renovated buildings may contain stagnant water, that should be flushed out before returning the building to normal use.

|

|

WATER PRESSURE |

|

|

BIOFILM, SCALE AND SEDIMENT |

· Legionellae have been found in biofilms forming on plastic surfaces in water piping systems. At a temperature of 40° they were shown to account for approximately 50% of the total biofilm flora; · Legionellae are less likely to be present on copper surfaces because copper generally do not support biofouling. If present, the bacteria are usually found in small numbers; · Metal plumbing components and associated corrosion products provide iron and other metals needed for Legionella, thereby supporting their survival and growth.

Algal slime also provides a stable habitat for their survival and multiplication.

|

Disinfectants After disinfection, municipal water supplies usually travel several kilometers before it reaches the point of use. During this course, disinfectant residuals diminish and there is increasing exposure to potentially biofilm-contaminated piping. Although municipal water systems are required to be disinfected at their points of distribution to conform to existing standards for bacterial disinfection, these standards are based upon the absence of coliform bacteria and do not include any specific testing requirements for Legionella.

Transmission

After growth and amplification of legionellae to potentially infectious levels, the next requirement in the chain of infection is to achieve transmission of the bacteria to a susceptible host. Modern technology like cooling towers used to recirculate water for air-conditioning and humidifying purposes and other ventilation systems can cause the formation and distribution of aerosols through which the organisms can spread. Transmission can also occur through direct installation, aspiration or ingestion (Table Dissemination of Legionella bacteria).

|

AEROSOLISATION |

|

|

DIRECT INSTALLATION |

|

|

INGESTION |

|

|

ASPIRATION |

|

INFECTION AND HOST SUSCEPTIBILITY

Infections caused by Legionella species are collectively known as legionellosis and include Legionnaires’ disease and Pontiac fever. Subclinical (asymptomatic) infections have been reported. Legionellosis occurs worldwide, in people of all ages and race groups, with no evidence of person-to-person spread of infection. It is most common in summer and autumn months. The incidence of legionellosis varies from country to country and from region to region. Recently, an increase in the worldwide incidence of reported legionellosis cases has become evident. This may be explained by the availability of improved diagnostic and testing methods, increased awareness of the symptoms and improved surveillance. However legionellosis, especially sporadic cases, is still not always reported to public health authorities, making it difficult to estimate its true incidence.

The mode of transmission, inoculum size, particle size and host susceptibility influence the severity of infection. Approximately half of the currently known Legionella species are implicated in disease, but pneumophila is still considered to be the causative agent in about 80% of diagnosed cases. However, this picture might change as the number of available diagnostic tests increases – it is thus important to regard all legionellae a potentially pathogenic until proven otherwise.

Section 3

LEGIONELLA INFECTIONS

Infections caused by Legionella species are collectively known as legionellosis and include Legionnaires’ disease and Pontiac fever.1,2 Subclinical infections have been reported. Legionella infections occur worldwide in people of all ages and race groups with no evidence of person-to-person spread of infection.3,4

LEGIONNAIRES’ DISEASE

Legionnaires’ disease (LD) is a severe multisystem disease with pneumonia as the most predominant clinical finding. Clinical features are similar to those of other pneumonias, making it difficult to diagnose.5,6 Symptoms range from a mild cough and slight fever to a coma with widespread pulmonary infiltrates and multisystem failure. Survivors usually recover completely although lung fibrosis and neurological abnormalities may persist in some cases. LD has a low attack rate but the mortality rate is high.

Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks occur frequently all over the world. In the United States, Legionnaires’ disease is considered to be fairly common and legionellae are among the top three causes of sporadic, community-acquired pneumonia. However, many cases are still not reported, as Legionnaires’ disease is difficult to distinguish from other forms of pneumonia. Although only approximately 1,000 cases are reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), it is estimated that over 25,000 cases occur every year, causing more than 4,000 deaths.

Despite this, only one outbreak has been reported in South Africa to date. However, previous South African studies indicated antibody levels to L pneumophila in 65% of healthy blood donors, 36% of healthy mineworkers, 10% of healthy factory workers and 16% of hospitalised pneumonia patients.7,8 One study reported seroconverion to L.

pneumophila in 9% of patients hospitalised between 1987 and 1988 with symptoms of community-acquired pneumonia.9

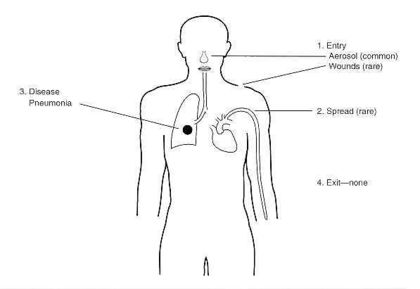

Figure 3.1 Legionella pathology

3.1 RISK FACTORS

In order for LD to occur, the host must be susceptible to infection. Older people (above 50 years of age) are more commonly infected. Men are more likely to be infected (ratio 3:1) but the racial distribution is usually consistent with that of the population involved.10

Table 3.1 lists the most common risk factors.

| Table 3.1 Risk factors for development of Legionnaires’ disease | |

|---|---|

| Patient demographics | Smoking

Chronic pulmonary disease Immunosuppression Renal transplantation Renal dialysis Alcohol ingestion Age > 50 years Male |

| Environmental risks | Exposure to construction activities

Exposure to air conditioning systems Exposure to home air conditioning Travelling and accommodation in hotels Potable water Hospitalization |

Source: Winn 1984 10

3.2 SYMPTOMS

Legionnaires’ disease presents with a broad spectrum of symptoms, ranging from mild cough and low fever to stupor, respiratory and multi organ failure. Pneumonia is the predominant clinical finding. Early symptoms are mainly non-specific and include fever, malaise, myalgias, anorexia and headache.6,11 The temperature often exceeds 40°C and the patient may present with a slightly productive cough. Chest pain, occasionally pleuritic, can be prominent and when coupled with hemoptysis, may mistakenly suggest pulmonary emboli. Gastrointestinal symptoms (watery stools) are prominent, especially diarrhoea, which occurs in 20-40% of cases. Relative bradycardia has been over-emphasised as a diagnostic finding but is often seen in elderly patients with advanced pneumonia. Hyponatremia (serum sodium concentration ≥ 130 mmol/l) occurs more frequently in Legionnaires’ disease than in other pneumonias.

Extrapulmonary Legionnaires’ disease is rare but the clinical manifestations are often dramatic. These infections can easily be overlooked since the degree of suspicion is generally low in these cases. Legionella has been implicated in cases of sinusitis, cellulitis, pancreatitis, peritonitis and pyelonephritis. The most common extrapulmonary site of infection is the heart. There have been numerous reports of myocarditis, pericarditis, postcardiotomy syndrome and prosthetic valve endocarditis. In most cases there is no pneumonia symptoms present. Wound infections have also been reported.11

3.3 INCUBATION PERIOD

LD has an incubation period (the time it takes for symptoms to appear after exposure) of 2 – 10 days. The onset of symptoms may be sudden or gradual.

3.4 DIAGNOSIS

There are no reliable distinguishing clinical features to distinguish LD from pneumonia caused by other etiologic agents. However, there are some clinical clues to assist in the diagnosis (Table 3.2).6

| Table 3.2 Clinical clues to Legionnaires’ disease | |

|---|---|

| CLUE | EXAMPLE |

| PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION | |

| Presence of an epidemic or documented source of infection | Family, friends or associates with similar infection and exposure |

| Prominent neurologic or gastrointestinal symptoms | Pneumonia with confusion, nausea and vomiting |

| Non-response to aminoglycosides or beta-lactam antibiotics | Worsening condition after 5 days on antibiotics |

| LABORATORY RESULTS OF PATIENT | |

| Gram stain of sputum with many neutrophils but no bacteria | Laboratory reports showing many neutrophils and few normal flora or no bacteria |

| Nodular peripheral infiltrates in chest radiographs | Progression of unilateral opacities to bilateral nodular infiltrates over several days |

It is important to remember that a clinical diagnosis of LD always has to be confirmed with specialised laboratory tests. As not all laboratories are equipped to perform these tests routinely, the tests have to be specifically requested by the physician. Table 3.3 highlights some of the most commonly used laboratory tests.12

- Culture of Legionella organisms from clinical samples is still the gold standard for diagnosing LD. The technique is highly specific, provided appropirate samples are used, and about 1.5 to 3 times more sensitive than immunofluorescence. Transtracheal aspirates are best for culture, but sputum, bronchial aspirates, pleural exudates, lung biopsies as well as wound swabs and even autopsy material have been used successfully.11 Disadvantages of the culturing of legionellae for diagnostic purposes include possible inhibition by non-legionellae organisms present in the sample, slow growth and difficulties in distinguishing legionellae from other organisms on solid media. These factors must be taken into account when choosing a laboratory to test clinical samples for LD.

- Immunofluorescence is useful to detect antigens (direct immunofluorescence) or antibodies (indirect immunofluorescence) in clinical samples in cases where culture is not possible. Cross reactions with organisms other than Legionella in the direct immunofluorescence (DFA) test may cause false positive results, making accurate interpretation of the results essential.11,13 Indirect immunofluorescence (IFA) is the most specific of the currently available serological tests for LD. It is reproducible, sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of especially L. pneumophila infections, but may be affected by several factors, including the method of antigen preparation, method of antigen fixation during preparation of the reagent, the class of immunoglobulin it is designed to detect and strain differences.14,15

- The Legionella Urinary Antigen test5 is a relatively inexpensive and rapid diagnostic test, but only detects infections caused by L pneumophila Serogroup 1. The test is commercially available as a radioimmunoassay (RIA) or an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). An advantage of this test is the relative ease with which urine samples can be obtained, especially in patients with a non-productive cough. Legionella antigens may persist in the urine of some patients for as long as one year.

- Serological tests are useful for epidemiologic studies but less valuable for physicians. Diagnosis by serology is based on a fourfold rise in antibody titre to ≥ 1:128 in paired samples (from the acute and convalescent stage of disease).13,15 However, the antibody response may not be detectable until 1-3 months after onset of illness. Single titres of ≥1:256 during convalescence in pneumonia patients is suggestive of legionellosis. Antibody screening should include both IgG and IgM because some patients may only have an IgM response.5

- Assays based on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have been used to detect legionellae in urine, broncho-alveolar lavage fluid and sputum. These tests are highly specific but not more sensitive than culture and are much more expensive to perform. Limitations of PCR tests include the possible presence of certain “PCR inhibitors” in sputum and blood samples. The major advantage of PCR is the rapidity of the test and the ability to detect species other than L pneumophila. PCR is not used routinely for the clinical diagnosis of LD.

| Table 3.3 Sensitivity and specificity of laboratory tests for the diagnosis of Legionnaires’ disease | ||

|---|---|---|

| TEST | SENSITIVITY (%) | SPECIFICITY (%) |

| Culture from clinical samples | 80 | 100 |

| Direct immunofluorescence (DFA) | 33-70 | 96-99 |

| Indirect immunofluorescence (IFA) | 40-60 | 96-99 |

| Urinary antigen detection | 70 | 100 |

Source: Stout and Yu, 1997

WHAT TO TAKE INTO ACCOUNT WHEN INTERPRETING LABORATORY RESULTS

- Both IgM and IgG should be measured simultaneously.

- Diagnostic IgM titres will provide an earlier diagnosis than IgG because they indicate a primary immune response.

- Results obtained by the IFA should always be interpreted in conjunction with the clinical presentation of the disease.

- Titres below the diagnostic level together with clinical manifestations may be useful for early provisional diagnosis of Legionnaires’ disease; but diagnosis by IFA is usually retrospective.

- The interpretation of the IFA should take into account the variation in the time of appearance of antibodies, the types of antibodies produced and the length of time the antibodies are detectable in sporadic cases, as well as the prevalence of antibodies in the population from which the patient comes.

- The type of reagents used for IFA tests may influence the results: ether-killed, formalin-killed or heat-killed antigens vary in sensitivity and specificity and this should be taken into account in the interpretation.

- False negative results may be reported because a long time is needed for seroconversion to occur and not all species and serogroups are detectable by this method.

- Seroconversion (a fourfold rise in titre to at least 1:128) is considered as a presumptive positive result.

- A single titre of 1:256 or higher is regarded as a presumptive positive result.

- Serological results should preferably be confirmed by culture.

- In communities with low antibody prevalence, a single titre of 1:128 may be diagnostic and where the prevalence is high, a single titre of 1:256 may still provide only presumptive evidence of infection.

- Low titres usually indicate past infections.

- When titres to multiple antigens are raised, the titre that is fourfold higher than the others is considered to be diagnostic.

- In epidemiological studies diagnostic titres are usually one twofold dilution higher than for sporadic cases.

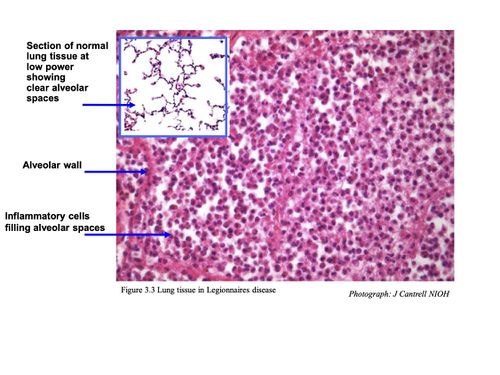

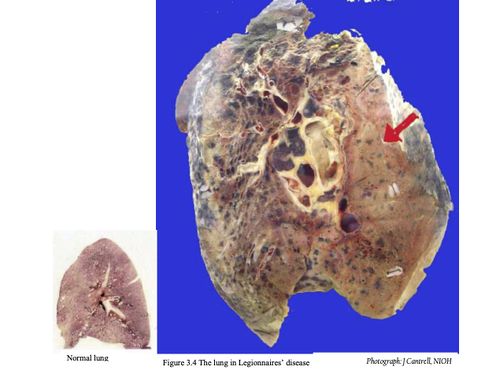

3.5 HISTOLOGY

Pulmonary lesions usually consist of a mixture of neutrophils and macrophages, fibrin, proteinaceous material and red blood cells. Neutrophils and macrophages are often present in the centre of a lesion with mainly macrophages around the periphery.

Intracellular bacteria are present in both neutrophils and macrophages. Further away from the site of acute inflammation, bacteria are mainly seen inside the macrophages.10

3.6 CHEST RADIOGRAPHS

Radiographic features in Legionnaires’ disease are mostly non-specific, and absent in Pontiac fever. Abnormalities occur from the third day post infection in most Legionnaires’ disease patients and usually do not correlate well with the severity of illness.11 However, the abnormalities correlate with the presence of the Legionella bacterium in sputum. The time required to show clearing of infiltrates on radiographs is variable and may range from 1-4 months. Some patients show diffuse alveolar damage. In the majority of patients with Legionnaires’ disease:

- Initial involvement is unilateral, predominantly in the lower lobe

- Bilateral involvement has been described

- Initial densities are poorly marginated, homogenous, rounded, occur either on the periphery or in the centre of the lung and may be mistaken for pulmonary infarction

- Pulmonary densities enlarge during later stages of disease

- Pulmonary densities have a typical ground glass appearance or dense consolidation

- Total opacification of the lung may occur

- Pleural effusions are present in 24-63% of cases caused by L pneumophila

- Pleural effusions are uncommon in L micdadei infections

- Hilar adenopathy seldom occurs

- Cavitation may occur in immunocompromised patients

- Cavitation rarely occurs in L micdadei infections

Figure 3.4 Chest radiograph of Legionnaires’ disease patient

3.7 TREATMENT

Treatment of LD requires the use of antibiotics. However, many antibiotics effective against other bacterial pneumonias are ineffective against Legionella as these drugs do not penetrate the pulmonary cells (alveolar macrophages) where infectious Legionella bacteria thrive.

Erythromycin was historically the drug of choice for the treatment of Legionnaires’ disease, but the newer macrolides (azithromycin) and quinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gemifloxacin, trovofloxacin have superior in vitro activity and greater intracellular and lung-tissue penetration.12 Other agents that have been shown to be effective include tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline, trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole.12 Rifampin is recommended as part of combination therapy with a macrolide or a quinolone for patients who are severely ill. The total duration of therapy is usually 10-14 days; however a 21-day course may be needed for immuno-compromised patients or those with extensive evidence of disease on chest radiographs.12

When LD patients are treated with appropriate antibiotics near the onset of disease, the prognosis is usually very good, especially if there is no underlying illness compromising the immune system. For patients with compromised immune systems, including transplant patients, any delay of appropriate treatment may result in complications, prolonged hospitalisation and death. However after successful treatment and hospital discharge, many patients still experience fatigue, loss of energy and difficulty concentrating. These symptoms may persist for several months, but complete recovery usually occurs within one year.

PONTIAC FEVER

Pontiac fever is an acute, self-limiting, flu-like illness without symptoms of pneumonia. The first outbreak of Pontiac fever was reported in Pontiac, Michigan, in 1968.16

It is characterised by high fever, chills, myalgia and malaise but without the pneumonia or cough typical of Legionnaires’ disease. Some authors suggest that it is a hypersensitivity pneumonitis, caused either by infection with a free-living amoeba called Acanthamoeba filled with legionellae or as a result of a toxic reaction to the organism. The incubation period is short, ranging from 1 – 3 days, and the attack rate high, exceeding 90% in some cases. The fatality rate is low.

Pontiac fever symptoms usually resolve spontaneously within one week, only symptomatic treatment is needed and the chest radiograph is clear. There is no evidence of secondary spread of the infection in Pontiac fever. Diagnosis can only be made by seroconversion, which may be delayed for up to 6 weeks after onset of symptoms. Cases of PF have been linked to L pneumophila, L feelei and L anisa. Complete recovery usually occurs in 2 – 5 days without medical attention.

References

- ↑ Dennis PJ (1993). Potable water systems: insights into control. In: Barbaree JM, Breiman RF and Dufour AP (eds). Legionella: Current status and emerging perspectives. American Society for Microbiology, Washington DC. Pp 223-225.

- ↑ Colbourne JS and Dennis PJ (1985). Distribution and persistence of Legionella in water systems. Microbiol. Sc. 2: 40-43.

- ↑ Muraca PW, Stout JE, Yu VL and Yee YC (1988). Mode of transmission of Legionella pneumophila. A critical review. Am. J. Hyg. Assoc. 49: 584-590.

- ↑ Yamamoto H, Sugiura M, Kusunoki S, Ezaki T, Ikedo M and Yabuuchi E (1992). Factors stimulating propagation of legionellae in cooling tower water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58: 1394-1397

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Freije MR (1996). Legionella control in healthcare facilities: A guide for minimising risk. HC Information Resources, Inc. United States of America. P 8

- ↑ MarrieTJ, Haldane D, Bezanson G and Peppard R (1992). Each water outlet is a unique ecological niche for Legionella pneumophila. Epid. Infect. 108: 264-270

References Chapter 3

- Dowling JN, McDaevitt DA, Pasculle AW. Isolation and preliminary characterization of erythromycin-resistant variants of Legionella micdadei and Legionella pneumophila. Agents Chemother. 1985, 27 (2): 272-274.

- MacFarlane JT, Miller AC, Smith WH, Morris AH, Rose DH. Comparative radiographic features of community acquired Legionnaires’ disease, pneumococcal pneumonia, Mycoplasma pneumonia and psittacosis. Thorax 1984, 39: 28-33.

- Boldur I, Beer S, Kazak R, Kahana H, Kannai Y. Predisposition of the asthmatic child to legionellosis? Isr. J. Med. Sci 1986, 22 (10): 733-736.

- Kurtz JB. Legionella pneumophila. Am. J. Occup. Hyg. 1988, 32 (1): 59-61.

- Shapiro M. Unusual epidemiologic and clinical manifestations of legionellosis: a review. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 1986, 22 (10): 724-727.

- Yu VL. Legionella pneumophila (Legionnaires’ disease). In: Mandell, Douglas and Bennet (eds). Principles and practice of infectious disease. 1990, Third Edition, Churchill Livingstone.

- Ratshikhopha ME, Klugman KP, Koornhof HJ. An evaluation of two indirect fluorescent antibody tests for the diagnosis of Legionnaires’ disease in South Africa. South African Med. J. 1990, 77: 392-395.

- Bartie C and Klugman KP. Exposures to Legionella pneumophila and Chlamydia pneumoniae in South African mine workers. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 1997, 3: 120-127.

- Maartens G, Lewis SJ, de Goveia C, Bartie C, Roditi D, Klugman KP. “Atypical” bacteria are a common cause of community acquired pneumonia in hospitalised adults. South African Med. J. 1994, 84: 678-682.

- Winn 1991

- Roig J, Aguilar X, Ruiz J, Domingo C, Mesalles E, Manterola J, Morera J. Comparative study of Legionella pneumophila and other nosocomial-acquired pneumonias. CHEST 1991, 99: 344-350.

- Stout JE, Yu VL. Legionellosis. New Engl. J. Med. 1997, 682-687.

- Ruf B, Schürman D, Horbach I, Fehrenbach FJ, Pohle HD. Prevalence and diagnosis of Legionella pneumonia: a 3-year prospective study with emphasis on application of urinary antigen detection. J. Inf. Dis. 1990, 162: 1341-1348.

- Harrison TG, Dournon E, Taylor AG. Evaluation of sensitivity of two serological tests for diagnosing pneumonia caused by Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. J. Clin. Pathol. 1987, 40: 77-82.

- Pastoris MC, Ciarrochi S, Di Capula A, Temperanza AM. Comparison of phenol- and heat-killed antigens in the indirect immunofluorescence test for serodiagnosis of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 antigens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1984, 20 (4): 780-783.

- Kaufmann AF, McDade JE, Patton CM, Bennett JV, Skalyi P, Feeley C, Anderson DC, Potter ME, Newhouse VF, Gregg MB, Brachman PS. Pontiac fever: isolation of the etiologic agent (Legionella pneumophila) and demonstration of its mode of transmission. Am. J. Epid. 1981, 114 (3): 337-347.