Healthcare Technology

Contents

- 1 Background

- 2 Life cycle of Health Technology

- 2.1 Planning

- 2.2 Needs assessment

- 2.3 Asset management

- 2.4 Budgeting & financing

- 2.4.1 Estimates of budget lines for equipment expenditure

- 2.4.2 Estimates of maintenance costs for forward planning

- 2.4.3 Estimates of consumable operating costs for forward planning

- 2.4.4 Estimates of equipment replacement costs

- 2.4.5 Rough estimates of equipment-related administrative costs for forward planning

- 2.5 Requisitioning

- 2.6 Procurement

- 2.7 Receipt, testing, installation & commissioning

- 2.8 Training

- 2.9 Operation

- 2.10 Maintenance, risk-management and safety

- 2.10.1 Introduction

- 2.10.2 Risk-based maintenance strategy

- 2.10.2.1 Data collection - equipment groups

- 2.10.2.2 Risk evaluation - factors impacting on risk

- 2.10.2.3 Risk ranking and risk classes

- 2.10.2.4 Inspection and preventive maintenance planning

- 2.10.2.5 Equipment supported

- 2.10.2.6 Method - maintenance procedures and intervals

- 2.10.2.7 Materials – service required items

- 2.10.2.8 Staff – human resource requirement

- 2.10.2.9 Maintenance intensity of specific equipment

- 2.10.2.10 Maintenance trade classification

- 2.10.2.11 Maintenance labour time requirement

- 2.10.2.12 Outsourcing of maintenance activities

- 2.10.2.13 Implementation of preventative maintenance plan

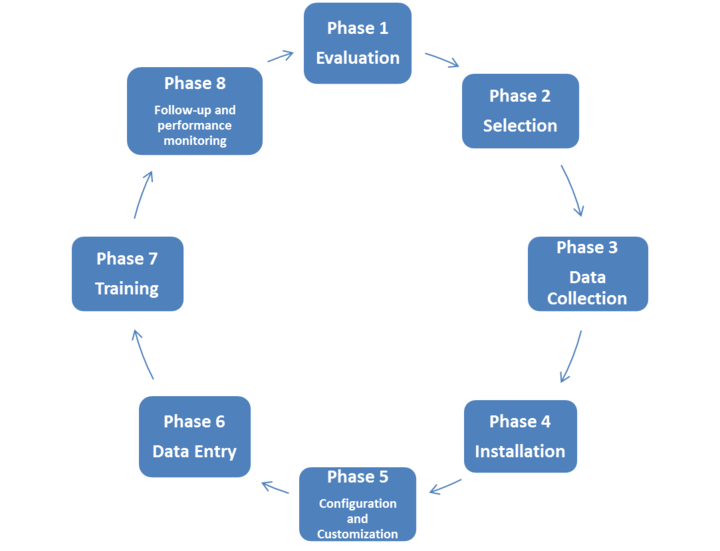

- 2.10.3 Computerised maintenance management system (CMMS)

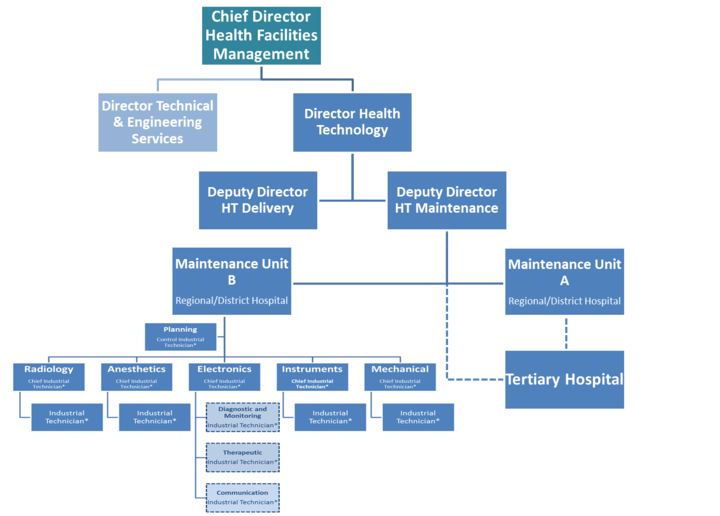

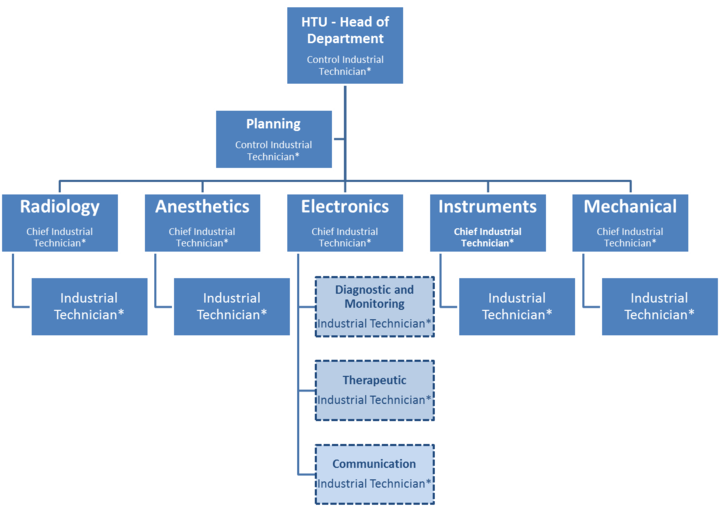

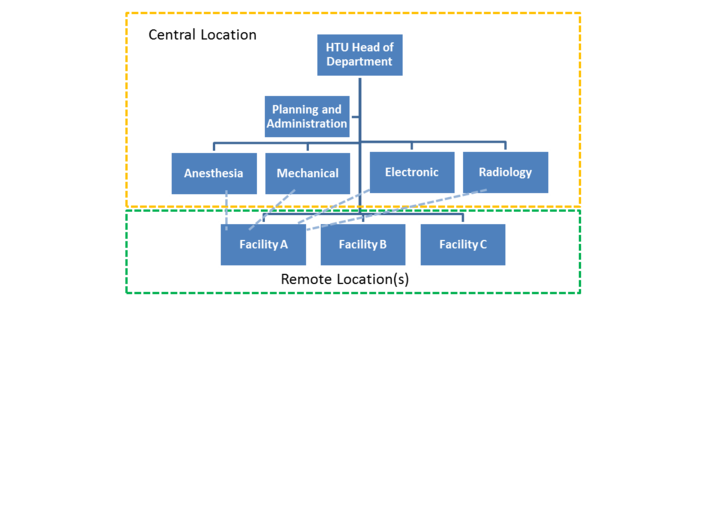

- 2.10.4 Human resources

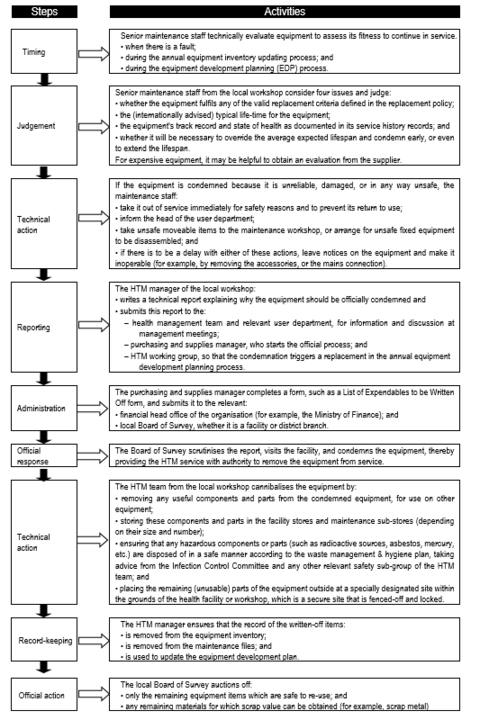

- 2.11 Replacement, decommissioning and disposal

- 2.12 Monitoring & evaluation of the HTM system

- 3 Annexures

- 3.1 Annex I: Sample Generic Equipment Specification: Infant Incubator

- 3.2 Annex II: Healthcare technology standards and indicators

- 3.2.1 Standards

- 3.2.1.1 HT Planning (S1)

- 3.2.1.2 HT Inventory (S2)

- 3.2.1.3 HT Budgeting and financing (S3)

- 3.2.1.4 HT Requisition (S4)

- 3.2.1.5 HT Procurement (S5)

- 3.2.1.6 HT Receipt, testing, installation & commissioning (S6)

- 3.2.1.7 HT-related training and skills development (S7)

- 3.2.1.8 HT operation (S8)

- 3.2.1.9 HT maintenance, risk management and safety (S9)

- 3.2.2 Indicators

- 3.2.1 Standards

- 3.3 References and selected bibliography

Background

Health technology context

Health Technology covers a wide range of apparatus, consumables, devices, equipment and instruments that would require many volumes of documents to cover effectively. This document, as part of the broader IUSS Norms and Standards project, aims to look at the key elements of Health Technology and its management as it manifests in healthcare facilities. The document specifically aims at framing the subject of Health Technology within the infrastructure development and operations domain.

The various definitions of Health Technology are listed in the Glossary but it is important to note that this document focuses on durable medical equipment and related consumables used in healthcare facilities. Hospital plant and machinery, normally associated with the building and most often installed as part of the building, are dealt with in various other documents in the IUSS document bouquet, either under the respective hospital engineering disciplines or under the respective clinical service area.

Application of the Guidelines

This document, published under the Health Facility guides, would be useful for practitioners of Health Technology Management both at the level of an individual facility and for groups of facilities (for example, in a district) and at any level of care. It would also be of great value for HTM practitioners and facility managers in general who might lack the first-hand experience of this relatively specialised field. In many cases the guidelines show the way towards developing specific and applicable solutions rather than being prescriptive. This approach is necessary to ensure that they remain sufficiently generic to be applied across a broad spectrum of scenarios. The document would also be of interest to health infrastructure professionals who might need specific insight into the domain of Health Technology and its management, recognising that technology and infrastructure are closely inter-related and will become ever more so in future healthcare systems.

This document should be considered in the context of the solid platform provided by the Health Technology Policy and the Health Facilities Planning Directorates of the National Department of Health. This includes the Framework for Health Technology Policies which outlines the vision of a National Health Technology System; the draft Health Technology Management Policy document which inter alia outlines the organisational and structural requirements at all levels of governance pertaining to such a system; the Health Technology Strategy which outlines specific objectives and activities, with associated timeframes, for establishing a National Health Technology System; the Report of the Interim Steering Committee on Health Technology Assessment, which underlines the importance of having formal processes in place to assess issues of health technology cost-effectiveness, access, service-fit and social impact, amongst other “evaluative dimensions”; and lastly the draft Medical Device Regulations and associated background documents which – in their final form – will be promulgated under the South African Health Products Regulatory Agency (SAHPRA) Act .

Life cycle of Health Technology

Planning

Introduction

Planning and budgeting are often considered jointly since planning – for it to be effective – needs to take place within the context of policy, financial, and other constraints. Box 1 shows the overall process.

BOX 1: The planning and budgeting process (start-up)

| Steps | People responsible | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Plan and budget within the framework of guidance and direction from the national level. | Health service managers at national level in consultation with managers at other levels. | Framework requirements

|

| Increase the availability of planning skills for equipment at all service levels, by developing planning “tools” through one-off exercises. | HTM working groups and sub-groups.

Finance officers. |

Knowing where one is starting from

|

| Health management teams.

|

Knowing where one is headed

| |

| Ensure realistic estimates are made for all equipment-related allocations at all service.levels, by using budgeting “tools” to calculate expenditures required. | HTM working groups and sub-groups.

|

Capital budget calculations

|

| Ensure realistic estimates are made for all equipment-related allocations at all service levels, by using budgeting “tools” to calculate expenditures required. |

HTM managers and their teams. Heads of section.

|

Recurrent budget calculations

|

| Use the tools to make long-term plans and budgets |

|

Long-term planning

|

| Review the plans and budgets annually, and monitor progress in order to improve planning and budgeting. |

HTM working groups and sub-groups. |

Annual planning

|

| Review the plans and budgets annually, and monitor progress in order to improve planning and budgeting. |

Heads of department and HTM managers.

teams. |

Monitoring progress

|

For healthcare technology to be managed effectively, a clear idea of healthcare delivery goals and targets is needed, as well as the context in which the technology is operating. Equipment should not be viewed in isolation – it is there for a purpose, and must be managed according to set objectives. For effective planning, access to a wide range of information and reference materials is needed, as well as a clear vision of the direction in which the health service is headed, plus identification of what equipment is required to help achieve the health service goals.

To inform the technology part of the debate, the HTM working group (at each level) should consider the equipment implications of the healthcare interventions suggested, and then offer technical advice to their health management team. Box 2 and Checklist 1 show some of the issues that the national, province/district- and facility level HTM working groups, respectively, should consider.

BOX 2: Baseline information on medical devices

| Medical device situation | Considerations | Result |

|

|

|

CHECKLIST 1: Equipment considerations for vision at national level

| Issues | Example |

|---|---|

| What expansion of services is necessary or feasible? |

|

| What are the implications in terms of staff, skills, resources, patient referral networks? |

|

| Are desired expansions financially affordable? |

|

| Do the services suggested fit into the overall health service in the country? |

|

Planning and budgeting when starting out

Box 3 shows the minimum requirements for a scenario for an HTM system in its infancy, where the initial focus is not on long-term forward planning, but concentration on planning and budgeting on a yearly basis. As the system matures, other elements for forward planning can be added.

Box 3: Minimum planning and budgeting requirements

| Planning and budgeting element | If just starting out |

| 1. Equipment inventory

2. Stock value estimates 3. Budget lines for equipment expenditures. 4. Usage rates for equipment-related consumable items. 5. Reference materials. 6. Developing the vision of service delivery for each facility type. 7. Standard Equipment Lists. 8. Purchasing, donations, replacement, and disposal policies. 9. Generic equipment specifications and technical data. 10. Capital budget calculations. 11. Recurrent budget calculations. 12. Equipment development plan. 13. Equipment training plan. 14. Core equipment expenditure plan. 15. Core equipment financing plan. 16. Annual equipment planning and budgeting. 17. Monitoring progress. |

1. Essential to have.

2. Useful to carry out this exercise later on when rough estimates needed for long-term forward planning. 3. This alteration to budget layout can be done later, but it will help with analysis. 4. Useful to do this exercise as it helps with calculation of specific (annual) estimates. 5. These can be developed over time. 6. Should have an understanding of this, even if full exercise not undertaken. 7. Initially, list of urgent equipment needs drawn up by departments can be used. Later on, Standard Equipment Lists obtained elsewhere can be used. 8. Essential to have. 9. Initially learn from others. Later, develop own. 10. Initially learn how to make specific (annual) estimates; only learn the rough estimation methods when undertaking long-term planning. 11. Initially learn how to make specific (annual) estimates. Only learn the rough estimation methods when undertaking long-term planning. 12. Use the basic equipment development planning process only, and only apply it to the short term. 13. Develop a straightforward one for the short term 14. Initially only plan annually (see below). 15. Initially only plan annually (see below). 16. Create annual actions plans and an equipment budget showing income and expenditure. 17. Undertake the basic elements only – progress with annual plans and tools, coping with emergencies, providing feedback. |

Needs assessment

Standard lists of equipment

Once the vision for the direction of health service delivery has been developed, the healthcare interventions and procedures to be offered will be known. Based on this information, the Essential Service Packages can be developed; these will translate the vision into:

- human resource requirements, and training needs;

- space requirements, and facility and service installation needs; and

- equipment requirements.

The tool used in the process of defining what equipment is needed for each healthcare intervention is the Standard Equipment List. This is:

- a list of equipment typically required for each healthcare intervention (such as a healthcare function, activity, or procedure). For example, health service providers might list all equipment required for eye-testing, delivering twins, undertaking fluoroscopic examinations, or for testing blood for malaria;

- organised by activity space or room (such as reception area or treatment room), and by department;

- developed for every different level of healthcare delivery (such as district, province) since the equipment needs will differ depending on the vision for each level;

- usually made up of everything including furniture, fittings and fixtures, in order to be useful for planners, architects, engineers and purchasers, and

- a tool which allows healthcare managers to establish if the Vision is economically viable.

The Standard Equipment List must reflect the level of technology of the equipment. It should describe only technology that the facility can sustain (in other words, equipment which can be operated and maintained by existing staff, and for which there are adequate resources for its use). For example a department could have:

- an electric suction pump or a foot-operated one;

- a hydraulic operating table or an electrically controlled one;

- a computerised laundry system or electro-mechanical machines; and

- disposable syringes or re-usable/sterilisable ones.

It is important that any equipment suggested:

- can fit into the rooms and space available. Reference should therefore be made to any building norms defining room sizes, flow patterns, and requirements for water, electricity, light levels and so on;

- has the necessary utilities and associated plant (such as the power, water, waste management systems) available for it on each site - if such utilities are not available, it is pointless planning to invest in equipment which requires these utilities in order to work; and

- can be operated and maintained by existing staff and skill levels, or for which the necessary training is available and affordable.

Usefulness of the standard equipment lists

A Standard Equipment List is an aid to the planning process. In order to plan what equipment to purchase, awareness of any shortfalls in equipment is needed. To determine such shortfalls, the Equipment Inventory needs to be compared with the Standard Equipment List. This will indicate whether any equipment is currently missing or needs to be purchased. Thus, the Standard Equipment List will assist in determining what equipment is:

- necessary;

- surplus;

- extravagant; and

- missing

in relation to the Vision for the service.

Responsibility for developing the Standard Equipment Lists varies from country to country. It is most important that this task is undertaken by a multidisciplinary team, so that decisions benefit from the skills and views of many disciplines, not just one or two. The health service planners at central/national level should consider developing Standard Equipment Lists in collaboration with staff from each level of the service, as indicated in Box 4 below.

| Who/which level? | Takes what action? |

| HTM working group at each level | Organises special meetings of different types of staff to work on the Standard Equipment List. Then reports back to the Health Management Teams. |

| National level | Takes the first step and runs specific exercises to establish the Standard Lists of Equipment for each clinical and support area, at each operational level. |

| Province/district level | Takes the second step and adjusts the list on a regional/district basis to cover local variations. |

| Facility level | Takes the third step and assesses:

- how they can provide the healthcare interventions; and - what numbers of equipment they require depending on how they organise their work. Organisational decisions influence the quantity of equipment. For example, the timing of clinics can reduce or increase the workload in the laboratory. Before ordering new equipment, its level of use will need to be assessed. |

Equipment development plan

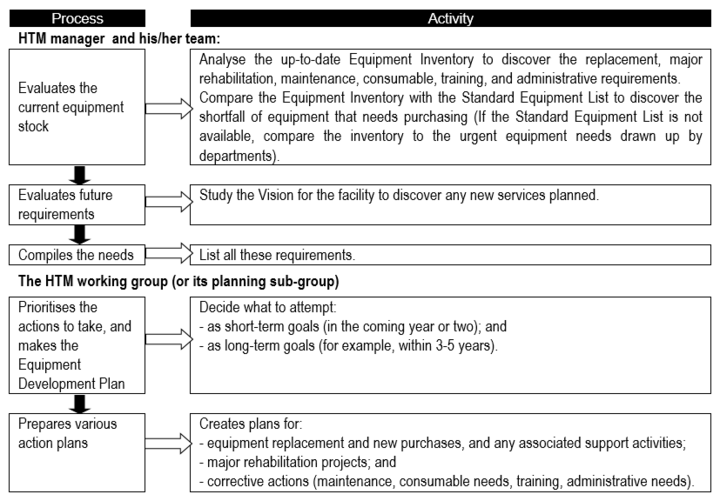

Especially for an HTM system that is not mature, it is essential to have important to have [BvR1] an equipment development plan; one suggestion for the development planning process is presented in Flowchart 1 below.

Flowchart 1: The basic equipment development planning process

Prioritising and appraisal of options

It is equally important, in the context of needs assessment, to critically examine the process and its outputs and outcomes. Checklist 2 below poses some key questions for consideration by the appropriate stakeholder/s.

Checklist 2: Key questions for prioritising and appraisal of options

Impact

|

Changeability

|

Acceptability

|

Resource feasibility

|

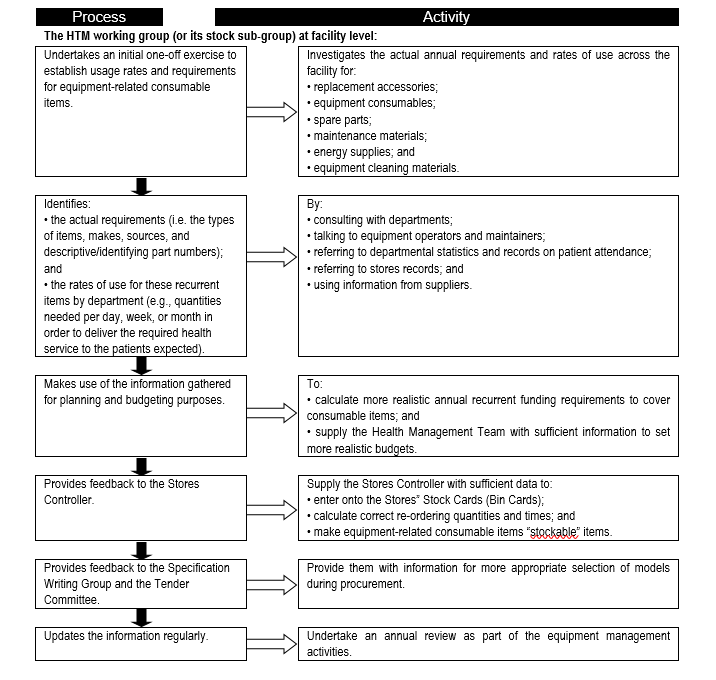

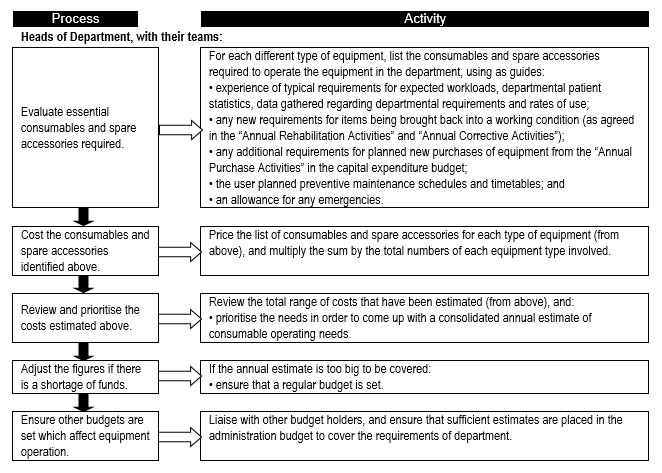

Consumables

Consumables are a major contributor to equipment-related cost of ownership, and form a significant portion of recurrent and operational expenditure. It is therefore important to establish the consumables needs so that adequate provision is made and service delivery is not interrupted. Flowchart 2 below suggests a process to facilitate the needs assessment related to equipment-related consumables.

FLOWCHART 2: Establishing usage rates and requirements for equipment-related consumable items

Asset management

Inventory

It is essential that an inventory (asset register) of medical equipment is maintained. However, it is both costly and time-consuming to include each and every medical device in an asset register. For those items in an asset register, the following information should be captured and verified:

- Equipment type (an international nomenclature system such as the Universal Medical Device Nomenclature System (UMDNS) should be used so that all institutions use a common name for the same type of device).

- Make/manufacturer.

- Model.

- Serial number.

- Date of acquisition.

- Price paid (include any costly accessories).

- Supplier details (name, address, contact person, contact details).

- Location – department or ward where the unit is used.

The responsibilities, activities and role-players relating to equipment inventory are shown in Box 5.

Box 5: Inventory-related responsibilities, activities and actors

| Body | Responsibility | Activity | People involved |

| HTM Service | Creates and updates the Equipment Inventory. | Organises the gathering of inventory data. | Either by:

|

| Inventory team | Visits each department in the health facility, and:

If existing records are available:

|

Due to the workload and knowledge required, it is useful for the team to be made up of:

| |

| HTM teams | Compile the Equipment Inventory.

Make hard copies. |

|

Make use of trained technical staff and secretarial/computing support to assist with data entry. |

| Central-level HTM team | Develops the Equipment Inventory as an active (regularly updated) resource. Analyses the Equipment Inventory for planning purposes. |

|

Makes use of support from staff trained in keeping computerised records. |

Asset management system

Proper asset management requires an appropriate information system which can be used to maintain data on those items that have been included in the asset register.

Equipment audits provide a snapshot of equipment status in a facility or groups of facilities, and can be aggregated to reveal the situation at national level. Audit data also serves to inform decision making related to needs assessment, asset management, maintenance strategies, replacement planning, and so on.

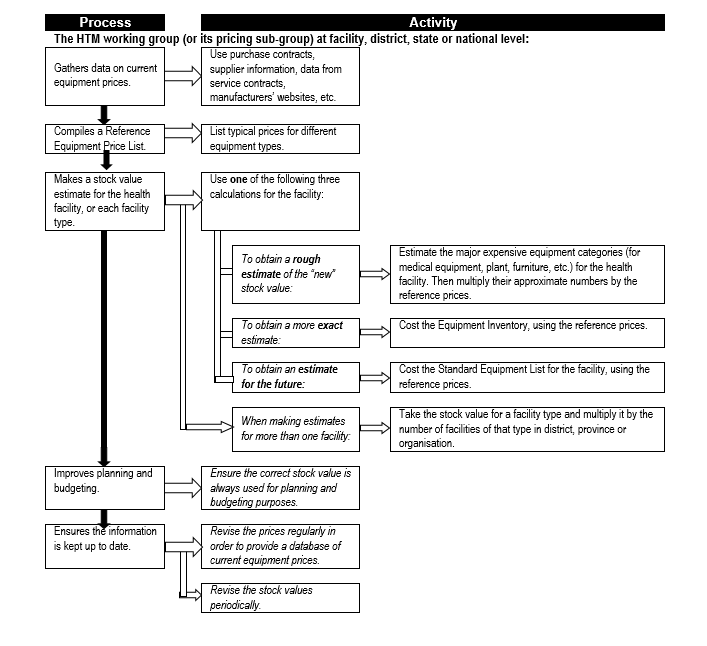

Also, once an inventory system is up and running, it will be necessary to periodically obtain estimates of total equipment stock values – this is used, for example, in benchmarking the total expenditure on maintenance. Flowchart 3 below shows the process for obtain such estimates.

Asset management software

It is essential to adopt and standardise on an appropriate asset management information system. There are a number of such systems available; serious consideration should be given to open-source solutions and/or or solutions which are cost-effective and sustainable, requiring minimal support.

Flowchart 3: How to estimate total equipment stock values

Budgeting & financing

Estimates of budget lines for equipment expenditure

It is essential to have budget lines for health technologies/medical equipment in national, province, district and facility budgets. A process for developing budget lines is shown in Box 6.

Box 6: Process for developing budget lines for equipment expenditure

| People responsible | Action |

| Finance officers, at all levels of the health service (central, province, district, facility) | Establish different budget lines (sub-divisions) as itemised below:

a. capital funds to cover equipment replacement (depreciation); b. capital funds to cover additional new equipment requirements; c. capital funds to cover support activities which ensure equipment purchases can be used (installation, commissioning, and initial training); d. capital funds to cover pre-installation work for equipment purchases; e. capital funds to cover major rehabilitation projects; f. recurrent funds to cover equipment maintenance costs, including spare parts, service contracts, and minor works; g. recurrent funds to cover equipment operational costs, including consumable items and worn out accessories; h. recurrent funds to cover equipment-related administration, including energy requirements; and i. recurrent funds to cover ongoing training requirements. |

| HTM working groups | Start using these budget lines to analyse how money is allocated and spent for equipment purposes. |

| Health service providers | Ensure that budgets are presented by cost centre so that it is clear what allocations are made between national, provincial, district and facility levels. In this way, it can be seen what money is spent on equipment activities at each level of the health service. Lobby other bodies involved (such as Ministries of Finance, Public Works) to also show equipment expenditures to establish what is allocated by other agencies for equipment activities in the health service. |

The high-level budgets thus obtained can then be “unpacked” into more detailed line expenditures, such as shown in Table 1 below, with projections covering 3-5-year budget cycles.

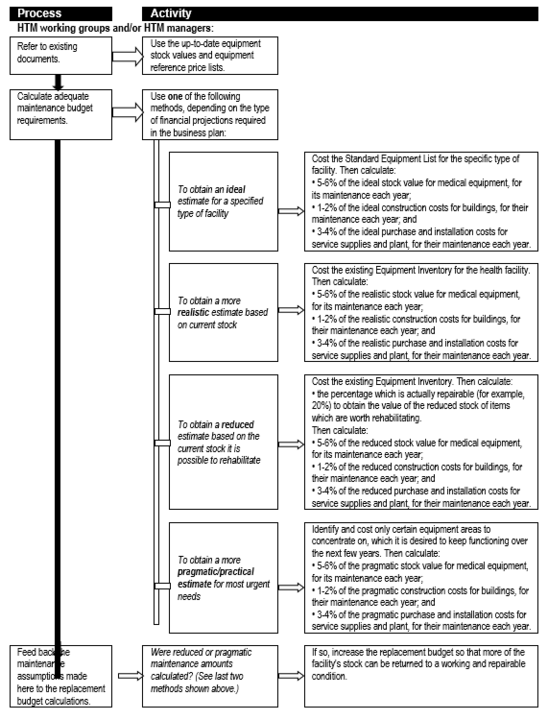

Estimates of maintenance costs for forward planning

An important – and often neglected – expenditure category is that of maintenance, be it for medical equipment or healthcare technologies and infrastructure in general. Box 7 unpacks the maintenance line item to indicate the various categories of maintenance-related expenditure for medical equipment, while Flowchart 4 suggests a process for estimating maintenance costs as part of planning.

Table 1: Example of a core equipment expenditure plan

| Capital expenditure | Short term | Medium term | ||

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Replacement | Use calculations for rough estimations (see Note below) | |||

| New equipment | ||||

| Support activities linked to purchases | ||||

| Pre-installation | ||||

| Rehabilitation | ||||

| Sub-total | ||||

| Recurrent expenditure | ||||

| Equipment maintenance | Use calculations for rough estimations (see Note below) | |||

| Consumables | ||||

| Administration | ||||

| On-going training | ||||

| Sub-total | ||||

| Total expenditure | ||||

Note: Initially, rough estimates are used for the short- and long-term overview when preparing this Core Equipment Expenditure Plan. During annual planning the estimates are revised, using calculations for specific requirements, to obtain the Annual Equipment Budget. The experience gained from that annual revision process may mean that the long-term estimates in this Core Equipment Expenditure Plan may have to be altered, so that they are more realistic.

Box 7: Elements of annual maintenance budgets

|

I. Planned budgets: These allocate funds for anticipated maintenance costs, which can be derived from the following main areas of expenditure: a) spare parts – which are required regularly, determined from previous experience and any planned remedial work; b) spare parts – which are required according to planned preventive maintenance (PPM) schedules and timetables; c) maintenance materials – which are required regularly, determined by previous experience and any planned remedial work; d) maintenance materials – which are required according to PPM schedules and timetables; e) service contracts – required for any planned remedial work; f) service contracts – for breakdowns which are likely to be required, determined from previous experience; g) service contracts – required for PPM of complex equipment; h) calibration of workshop test equipment; i) replacement of tools at the end of their life; j) office material; and k) any increased maintenance requirements brought about by planned new equipment purchases under the capital expenditure budget. Note: there will be other elements which may fall under other budgets. These could include:

|

|

II. Contingency budgets: In addition to planned budgets, contingency budgets also exist. These allocate funds for unplanned maintenance work, such as emergencies, or sudden breakdowns which could not be predicted. |

Flowchart 4: How to make rough estimates of maintenance costs for forward planning

Estimates of consumable operating costs for forward planning

In Section A2 (Needs assessment) the importance of consumables for proper functioning and utilisation was highlighted. Since medical devices cover such a wide spectrum, the related consumables require insight and good management. A number of alternative approaches are suggested:

i. Consumption depends on the type of equipment used, the service provided, and how many patients are seen. Therefore, a rough estimation of consumable operating costs can be obtained by evaluating past usage rates/expenditures, and comparing these with expected patient loads and specific equipment usage rates per intervention.

ii. If the equipment is part of a “closed” purchasing system, the consumables are only made by one manufacturer and one is limited to a single supplier; this monopoly often increases the consumable costs. If the equipment is part of an “open” purchasing system, anyone can supply the consumables and different manufacturers’ consumables could be used; this competition brings down costs of consumable. Costs can also be kept down by using items which can be sterilised/re-used.

iii. Consumable operating costs vary according to equipment type, and can be expressed as a percentage of purchase cost or stock value, as shown by the examples below. But as the majority of equipment is likely to be technology that has low to medium consumable costs, one could use averages of 3% of the stock value for equipment with low consumable usage rates, and for others as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Rough estimates of consumables’ operating costs for forward planning

| Description | Consumable cost per year (relative to original purchase cost) |

Equipment with high consumable operating costs, such as:

|

70-120% |

Equipment with medium consumable operating costs, such as:

|

20% |

|

15-25% |

|

10-15%

5-15% |

Equipment with low consumable operating costs, such as:

|

2-5% |

|

1-2% |

A different calculation is required when making specific or annual estimates. Annual operating budgets should be based on more exact estimates. These are not always easy to predict since epidemics, outbreaks, or surges in workload cannot, in most cases, be anticipated.

Generally with experience, and where standardisation of equipment is in place, the projection for equipment consumables and spare accessories becomes more predictable.

Specific or annual estimates of consumable operating costs

It is equally important to make provision for consumables on an annual basis. Flowchart 5 suggests how this could be done.

FLOWCHART 5: How to make specific or annual estimates of consumable operating costs

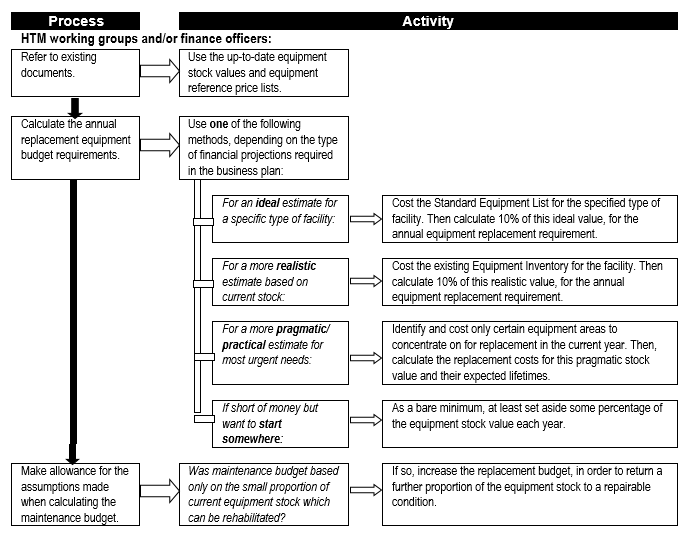

Estimates of equipment replacement costs

Equipment replacement needs to be provided for, especially in the case of complex and expensive equipment, to ensure that adequate resourcing is available at the appropriate time to ensure continuity – or at least minimal disruption – of service delivery. Flowchart 6 below suggests a process to establish estimates for replacement costs.

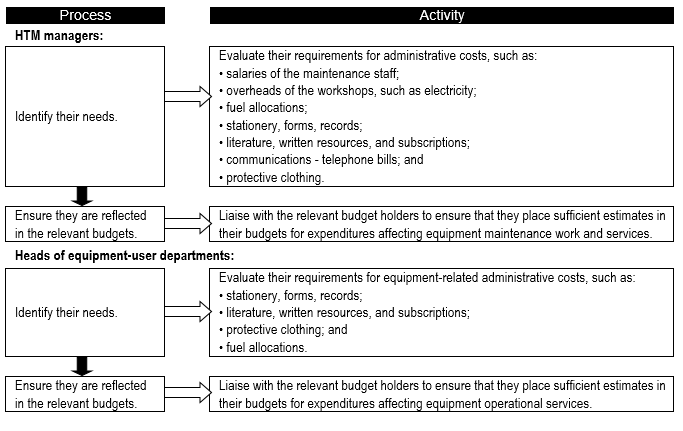

The administrative costs associated with medical equipment are also seldom considered separately, since they are hidden within general overheads. Different countries suggest alternative approaches:

i. Administrative costs are a small percentage of any operating budget; for example:

- the biggest percentage expense is for staff, taking 50-55%;

- supplies/spares take 35-45%; and

- administration takes only 10-20%.

Thus an equipment-user department could use an average of 15% of their its total operating budget for administrative costs.

ii. For HTM teams and clinical engineering service maintenance workshops, their administrative needs are not much higher than other administrative units in health facilities. Therefore, a reasonable estimate for the administrative costs[1] for HTM teams could be calculated by taking 10-20% of their total operating budget.

iii. A starting point is to use 5% of the equipment stock value to cover equipment-related administrative costs.

FLOWCHART 6: How to make rough estimates of replacement costs for forward planning

As in the case of consumable-related costs, it is important to determine the annual equipment-related administrative costs (Flowchart 7).

FLOWCHART 7: How to make specific estimates of assorted equipment-related administrative costs

Requisitioning

The following checklists cover three commonly encountered scenarios:

Checklist 3: Request to purchase new equipment that is not yet in use at the institution

a. Why is it essential to have this equipment and how will it enhance the present patient care. How was this function performed before and up until this request?

b. Statistics of the patients who will be treated with this equipment.

c. Is this equipment in line with the norms of the service delivery – level of care –of the institution?

d. Accessibility to similar equipment or services in a close proximity to the Institution.

e. Is suitable accommodation available to install the equipment (building and facilities). Is the structure suitable to carry the additional mass? This to be confirmed by the Engineering Services Manager, in writing.

f. Are there engineering services available to operate the equipment and has the availability of the service been confirmed in writing by the Engineering Services Manager, for instance:

- sufficient water pressure and flow (hot and cold);

- sufficient water pressure and flow (hot and cold);

- medical gas and compressed air (at the correct pressures and flow);

- sufficient power at the correct voltage and current levels;

- if required, a UPS system with a sufficient capacity;

- a power line-conditioning unit for sensitive electronic equipment;

- if required (for example autoclaves), is steam, condensate return and drainage available; and

- if required, is the ventilation and air-conditioning sufficient.

g. Are proper specifications available from the HTM unit or is suitable equipment available from an approved period tender? State the tender and the item numbers.

h. Confirmation must be obtained from the Institution that they have a budget (sufficient funds) to pay for a service contract (where called for), as well as consumables and preventive and corrective maintenance of the new equipment.

i. Will not having the equipment in any way compromise patient care or safety?

Checklist 4: Request to replace existing equipment

a. Inventory of similar equipment available in the Institution.

b. Inventory of how many pieces of the type of equipment are functional.

c. Inventory of how many pieces of equipment are not functional and the reason thereof.

d. Is this equipment in line with the norms of service delivery – level of care – of the institution?

e. Reason for the condemning of the equipment, supported by a Condemning Certificate.

f. Where the replacement is a fixture for instance an x-ray machine or processor, what engineering or structural changes will be required?

g. Does the Institution have sufficient funds to purchase the equipment requested?

h. Does the Institution have a budget, sufficient funds to pay for a Comprehensive Service Contract for the equipment requested?

i. Is suitable accommodation available to install the equipment (building and facilities) and is the structure suitable to carry the additional mass? This to be confirmed by the Engineering Services Manager, in writing.

j. Are there engineering services available to operate the equipment and has the availability of the service been confirmed in writing by the Engineering Services Manager, for instance (as for above scenario – Checklist 5)?

k. Can this equipment be standardised for the reasons previously stated above?

l. Statistics of patients to be treated with the equipment requested.

m. Are there no other procedures available to treat the patients?

n. Will not having the equipment in any way compromise patient care or safety?

o. Are there proper specifications from the Health Technology Unit available, or is suitable equipment available from an approved period tender? State the tender and the item numbers.

Checklist 5: Request to purchase additional equipment similar to equipment already in use

a. Inventory of similar equipment available in the Institution.

b. Inventory of how many pieces of the type of equipment are functional.

c. Inventory of how many pieces of the type of equipment are not functional and the reason therefore.

d. Is this equipment in line with the norms of service delivery – level of care - of the institution?

e. Reason for requesting the additional equipment backed up with patient statistics. Has the function or status of the Institution changed?

f. Does the institution have sufficient funds to purchase the equipment?

g. Does the institution have a budget, sufficient funds to pay for a comprehensive service contract for the equipment requested?

h. Can this equipment be standardised for the reasons previously stated?

i. Are there no other procedures available to treat the patients?

j. Will not having the equipment in any way compromise patient care or safety? Are there proper specifications available from the Health Technology Unit or is suitable equipment available from an approved period tender. State the tender and item numbers?

Procurement

Introduction

Procurement, from a healthcare service perspective, is probably the most important activity within the medical equipment life-cycle. If the right (competent) people are driving a transparent, criteria-driven (not interest-driven) process, it is likely that the healthcare system will avail itself of the technology that is most appropriate to the intended application, while addressing issues around effectiveness, cost-of-ownership, institutional fit, technology maturity and compatibility, user competence, maintenance and so on. In many countries, procurement is being placed in the hands of generic supply-chain management personnel with little specialised knowledge of medical equipment specifically, and health technologies in general. It is therefore essential to ensure that a supporting environment is created to minimise the possibility of sub-optimal procurement outcomes.

Procurement (for capital equipment as opposed to consumables) should be seen as a process with two phases: one that commences with planning and needs assessment and ends with commissioning, and the other that extends over its operational lifetime and ensures that the equipment is provided with the necessary accessories, consumables, maintenance support, and so on.

There are four reasons for procuring equipment, each of which provides a different goal which will dictate when to acquire equipment. These can be placed in the following order of priority (see Box 8 below). Within each of the four categories shown, priorities will have to be set, and these can be based on appropriate indicators.

Box 8: Example of valid reasons and order of priority for purchasing of equipment

| 1. To cover depreciation of equipment. | Equipment is replaced as it reaches the end of its life and is taken out of service. This is necessary in order for the level of healthcare that is currently delivered to be sustained. [Note: This means that the size of the existing equipment stock remains the same, and does not imply an expansion of the health service.] |

| 2. To obtain additional equipment items which are missing from the basic standard requirements. | Additional equipment may be required in order to provide a basic standard level of care. [Note: Missing items are identified by comparing the Equipment Inventory with the Standard Equipment List for the facility.] |

| 3. To obtain additional equipment items beyond the basic standard. | This is done in order to upgrade the level of health service provided by the hospital. For example, new equipment may be needed to provide a new service, build a new special unit, or increase the level of care offered. |

| 4. To obtain additional equipment items outside the facility’s own plans. | This will only be applicable if the additional items have been called for by directives from the national or provincial ministry, and cannot be stopped/refused for political reasons, such as “out of the ordinary”, high profile, or political projects. |

Of course, procurement is not a self-contained, isolated process but links up with many other equipment-related processes; these are shown in Box 9 below.

Box 9: Planning tools that assist in deciding on procurement

| Planning tools | How they help |

| When replacing items: | |

| Replacement policy | Establishing and implementing this tool is much more likely to ensure that the necessary regular planned replacement of equipment takes place. |

| Equipment inventory and maintenance record system | These tools support identification of the need for replacement equipment at any time. For easy reference, estimated lifetimes for equipment could be entered into the inventory and could then prompt one when to purchase. The natural life of equipment is shortened by harsh environment, over-use, unskilled handling, neglect of maintenance and damage. Equipment malfunction and downtime also increase with the age of the equipment. Accordingly, cost-effectiveness decreases with age. |

| Replacement and condemnation criteria | These assist with judging when equipment has reached the end of its life, and therefore with identifying when equipment needs replacing. |

| Core equipment expenditure plan | Some of the equipment will have to be replaced every year, so it makes sense to spread budgeting for replacement over time. By allocating some money each year, one can avoid facing a large replacement bill later on. This tool should spread these costs over the long term. Equipment replacement needs can be estimated each year by assuming that each piece of equipment has an average lifetime of 10 years [1] - this means that on average 10% of equipment stock needs to be replaced each year. |

| Disposal policy and disposal procedures | When equipment is replaced, these tools will assist with the disposal of the old device or system. There may be government regulations regarding disposal that will provide additional information. |

| Stock- control system | Replacement equipment-related supplies should be purchased after an up-to-date stock take. Accurate stock control systems help with planning and ordering. |

| When buying additional new items: | |

| Equipment development plan, and annual purchase plan | New equipment should be purchased according to an annual purchase plan (drawn each year from a long-term equipment development plan). This is based on an up-to-date inventory and Standard Equipment List. Accurate inventory record-keeping helps with planning and ordering. |

| Package of inputs | Planning in advance for what will be needed after the purchase is every bit as important as the purchase itself. Thus, one must ensure that the package of inputs required to keep equipment functioning through its life is procured. |

| Core equipment financing plan, and annual budget | Capital expenditure can only take place once sufficient funding sources have been identified. The long-term Core Equipment Financing Plan and Annual Budget should allocate known and possible sources of funds against elements of planned expenditure. |

Additional items of equipment may need to be procured to accompany/complement the original item, if it is to function properly in certain environments. For example:

- a voltage stabiliser (surge suppressor plus filter) - this offers protection against power supply fluctuations, but does not protect against power cuts. It monitors the power supply, removes surges and spikes, and maintains a continuously regulated alternating current output to the item;

- an uninterruptible power supply - this offers protection against blackouts and power cuts of limited duration;

- an air-conditioning unit; and

- a water filter or treatment plant.

Preparation of specifications

Specifications have to be drawn up for every device that is planned to be purchased. Standardised specifications need to be drawn up for commonly used devices which can then be modified (where necessary) at institutional level.

General terms and conditions should also be part of specifications, including stipulations like the local availability of essential spare parts, and the presence of a registered sole agent for the specific brand.

Specifications should be functional specifications and drawn up based on features available in at least a few brands of the device commonly available in South Africa. Before making a selection the following may be considered:

- demonstration of devices by supplier;

- trial use of the device in a facility;

- visit to a facility where the device is available;

- verbal presentation on device made by a supplier of the device; and

- communication with existing users of the device both locally and abroad.

A suggested format for specifications is as follows:

- name of equipment;

- Function;

- essential features;

- essential components;

- additional components;

- power supply;

- additional requirements; and

- training – user training, maintenance training.

In order to eliminate the possibility of outdated specifications being used, all specifications should have a validity date on the document. Specifications that are not valid or have expired should not be used. Copies of the latest specifications should be obtained from the appropriate HTM unit.

A sample specification (that for an infant incubator) is given in Annex I. For some equipment, such as sophisticated or imported items, or equipment which is new in the system, it may be necessary to specify the following item lines:

- Site preparation details – supplier should provide technical instructions and details so that this work can be planned, either in-house or by contracting out.

- Installation – assistance may be needed.

- Commissioning – assistance may again be required.

- Acceptance – the responsibilities of both the purchaser and supplier with respect to testing and/or acceptance of the goods must be clearly detailed.

- Training of both users and technicians – help must be obtained if required.

- Maintenance contract (an important part of after-sales support) – help must be requested if it is required. It will be necessary to agree and stipulate the duration, and whether it should extend beyond the warranty period, the cost and whether it includes the price of labour and spare parts, and the responsibilities of the owner and supplier.

There are a number of technical and environmental factors that need to be taken into account. For example:

- If the area has an unstable power supply, is the supplier able to offer technical solutions (such as voltage stabilisers, an uninterruptible power supply)?

- Will the geographical location (such as height above sea-level) affect the operation of equipment (such as motors, pressure vessels)? If so, can the manufacturer adjust the item’s specific needs?

- Extremes of temperature, humidity, and dust may adversely affect equipment operation, and may require solutions such as air-conditioning, silica gel, polymerised coatings for printed circuit boards, and filters.

This information can be included within the generic equipment specifications. However, since much of the information is common to many pieces of equipment, some health service providers have found it simpler to develop a separate summary Technical and Environmental Data Sheet, which can be referred to in the purchase documents. This data sheet can be distributed to all suppliers, interested parties, trade delegations and other relevant bodies. Such a data sheet can be provided regardless of the length of specification or the procurement method used, ensuring that all parties are kept informed of prevailing national conditions which could affect the operation of equipment.

The following details should be included in a Technical and Environmental Data Sheet:

- Electricity supply – mains or other supply, voltage and frequency values and fluctuations.

- Water supply – mains or other supply, quality and pressure.

- Environment: height above sea-level; mean temperature and fluctuations; humidity; dust level; vermin problems, etc.

- Manufacturing quality – international or local standards required.

- Language required – main and secondary.

- Technology level required – manual, electro-mechanical or micro-processor controlled.

Evaluation and comparison process

The process of evaluation and comparison can often be time consuming. However, it is important to ensure that decisions for awarding contracts are not made simply on the basis of which items are the cheapest. During evaluation the items should be assessed against the requirements specified in the purchase document. The most common way to evaluate offers is to use an elimination process, where some offers are rejected at each stage. Offers should be judged against the following criteria:

- Compliance with requirements in the purchase document.

- Technical nature of the offer (part of the product selection criteria).

- Financial nature of the offer (part of the product selection criteria).

- Supplier qualification criteria.

By doing this, decisions are based on best value for money for the whole life-cycle cost, rather than simply being based on the item’s purchase price.

The process of evaluation and comparison must be fair and thorough. To achieve this, the process must follow a defined pattern to ensure all bids/quotes are dealt with in exactly the same way.

The evaluation process for tenders is similar to that for quotes, although the tender process is normally a far more comprehensive task and is also regulated by law. The tools for evaluation can be the same, but the amount of information required is usually much less with quotation methods. Obviously, if only three quotes are requested for a simple small order, the evaluation process should not take much time. The following evaluation steps are used, and some bids/quotes are rejected at the end of each step.

Step 1: Checking for compliance

The first step when evaluating offers is to determine which, if any, are not compliant with the technical, commercial, and other specifications in the purchase document. The procurement unit should be able to do this. It involves a more detailed examination of the offer to determine the compliance by the bidder with the requirements specified in the purchase document. This is known in tender processes as the substantial responsiveness of the bid. This process is more formal and comprehensive for tenders than for quotations.

A substantially responsive bid is one which:

- conforms to all the terms and conditions; this means that the supplier has responded to all parts of the schedule of requirements, has filled in all the boxes, and is able to supply all the parts required; and

- also establishes the bidder’s qualifications to supply and deliver the products within the delivery schedule; for example, the supplier:

- has enclosed signed audited accounts, signed company declarations on health, safety, and environmental activities, certificates of quality manufacturing, and a letter of authorisation from the manufacturer, and

- has nominated a representative in the country (if this was one of the compliance criteria).

All non-substantial bids will be rejected as non-responsive and should be excluded from further in-depth evaluation.

In practice it is found that most bids contain reservations from one or more of the detailed requirements. If these are just minor adjustments and do not represent a substantial deviation from expressed interests, one can still conclude that the bid is substantially responsive and therefore should be included. However, the reservations for closer clarification should be listed.

To assist in this examination one could ask for other clarifications from the bidder. One may also wish to inspect the quality methods and production methods stated in their documents. This request and response should be in writing. The bidders, however, are not allowed to make any changes to the substance or price of their offers. After evaluating the offers for compliance, some offers are discarded as the suppliers fail. The remaining offers can go forward to be compared in terms of technical performance (Step 3).

Step 2: Preparing the evaluation information

The procurement unit should collate and compile the information from all the responsive bids into evaluation information sheets. Box 10 gives an example of the sort of data that needs to be included.

Box 10: Evaluation information sheets

| Evaluation Information Sheets present an easy way to compare different bids/quotes. For ease of comparison, it is best to allocate one page per subject matter (technical product details, price, etc.) and compare the offers side-by-side. Areas where each offer deviates from the equipment specification should be highlighted. Typical evaluation information sheets would include the following evaluation criteria:

Accessories, consumables, spare parts:

After-sales service:

Price information:

Note: this is an example and not a comprehensive list. The information chosen to include will depend upon the complexity of the equipment purchased – less technical detail is needed for simple equipment or recurrent supplies. |

Ideally the evaluation information sheets should allow side-by-side comparison of the offers. For tenders there are more responses and the orders tend to be more complex, so more paperwork is required to obtain a true comparison. Usually there is too much information to be compiled in a single sheet, so it may be better to use:

- one sheet for collating purely technical information about the product;

- one for information on accessories, consumables, and spare parts;

- one for after-sales service; and

- one for price information.

The procurement unit should present the evaluation information sheets to the procurement/tender committee (for tenders and high-value quotes) or the Procurement Manager (for low-value quotes). They should be accompanied by an explanation of the requirements, main objectives, and any binding constraints. Then the technical evaluation process (Step 3) can commence.

Step 3: Carrying out the technical evaluation

The procurement/tender committee should base its decision on advice from members of the group with professional knowledge relevant to the offer. If appropriate, it should also seek advice from representatives from the relevant user department and HTM team (for low-value quotes, the Procurement Manager should also seek advice from these end-users).

The committee should consider the product selection criteria, as set out in the purchase document. It is essential that the information provided by the supplier is related only to the equipment specification and the selection criteria listed in the purchase document – any additional information intended to sway the evaluation can be seen as corruption; hence the importance of detailing requirements adequately in the purchase document. The better the purchase document, the easier the evaluation process will be. Box 11 lists a few points to remember, relating to the technical aspects of the offer.

Box 11: Summary technical assessment

|

For both quotations and tenders it may be necessary to ask the supplier to clarify any ambiguities or uncertainties. Alternatively, a shortlist of suppliers can be drawn up and those included can be asked to demonstrate their equipment, as part of the technical evaluation (this is unlikely to be necessary for very simple equipment, and may be impossible for many overseas suppliers).

After the technical evaluation, some offers are discarded if they fail to meet the requirements. The remaining offers can go forward to be compared in terms of financial performance.

Issues to consider when choosing equipment

Choosing equipment is not easy, due to the wide range of products available. External influences also play a part. For instance, external support agencies may impose their own conditions regarding suppliers, which may result in inappropriate equipment being supplied or procured. The acquisition policy should clearly specify the “good selection criteria” to employ. All equipment should:

- be appropriate to its intended target setting;

- be of assured quality and safety;

- be affordable and cost-effective;

- be easily used and maintained; and

- conform to the existing policies, plans and guidelines.

These criteria, unpacked in Checklist 6 below, should be used during the procurement process when evaluating and adjudicating between different offers from suppliers.

Checklist 6: Example of good selection criteria for equipment purchasing

| Indicators of appropriateness | Criteria |

| Appropriate to setting | Equipment should be:

|

| Assured quality and safety | Equipment should be:

|

| Affordable and cost-effective | Equipment should be:

|

| Ease of use and maintenance | Equipment should be chosen

|

| Conforms to existing policies, plans and guidelines | Equipment should be chosen:

|

It may also be appropriate to have a set of criteria to evaluate equipment suppliers, both current and past, as per Checklist 7.

Checklist 7: Suggested criteria for evaluating current and past suppliers

| Issue | Criteria |

| Participation record |

|

| Response to enquiry |

|

| Delivery time (for consumables) |

|

| Adherence to delivery instructions |

|

| Provisions of documents |

|

| Packing and labelling (mainly for consumables) |

|

| Product shelf life (for consumables) |

|

| Compliance with contract financial terms |

|

| Quality of products and services |

|

Adapted from: Management Sciences for Health, 2002, “Managing drug supply”, MSH, Boston, USA.

Donations

Donations are a special case of procurement, and great care needs to be exercised in managing the procurement process associated with donated equipment. The World Health Organization (WHO)[1] and other bodies have drafted guidelines to facilitate this process.

Receipt, testing, installation & commissioning

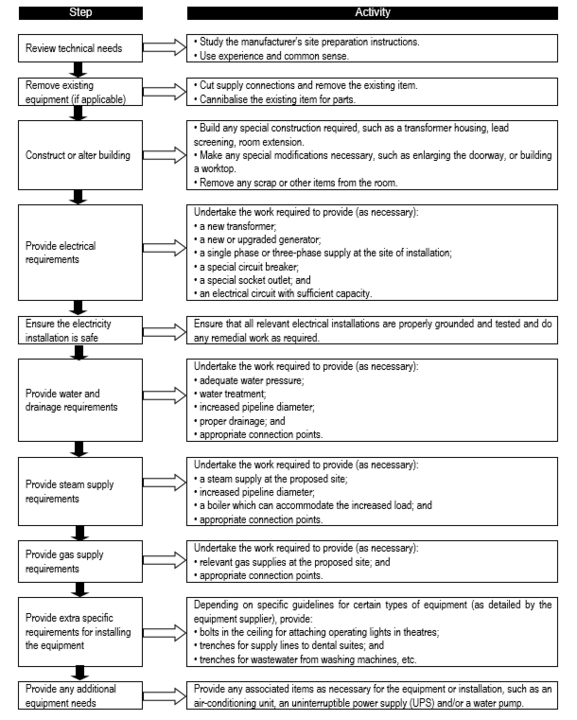

Pre-installation work / site preparation

The site at which the device is to be installed has to be adequately prepared, more so in the case of large, sophisticated devices like x-rays, autoclaves. This has to be coordinated with logistics of the device supply so that the site is ready when the device is delivered at the institution. The associated utilities like appropriate power supply, water, compressed air and the like, as well as other appropriate requirements like radiation protection should also be taken into consideration. In situations where extensive site preparation is necessary, like in x-rays or CT scans, site works should be included as part of the acquisition process to ensure comprehensive and coordinated site preparation.

Pre-installation work involves:

- preparing the site ready for equipment when it arrives;

- organising any lifting equipment;

- organising any warehouse (storage) space;

- confirming installation and commissioning details; and

- confirming training details.

In some cases, the pre-installation work required is minimal; in others it requires considerable labour and finance. As a general guide, site preparation is the work required to ensure that the room or space where the equipment will be installed is suitable. It often requires the provision of new service supply connections (for electricity, water, drainage, gas, waste) and may require some construction work. Site preparation tasks can include:

- disposing of the existing obsolete item (disconnection, removal, cannibalising for parts, transport, decontamination and disposal);

- extending pipelines and supply connections to the site, from the existing service installations;

- upgrading the type of supply, such as increasing the voltage, or the pipeline diameter;

- providing new surfaces, such as laying concrete, or providing new worktops; and

- creating the correct installation site – for example, digging trenches, building a transformer house or a compressor housing.

In considering where to position equipment, the following types of questions should be asked:

- Is there sufficient access to the room/space? (Door sizes and elevator capacity are very important for x-ray and other large machines.)

- Is the room/space large enough?

- Is the position and layout of the room/space suitable?

- Are the required work surfaces and service supply points available?

- Is the environment adequate for the purpose? (For example, is it air-conditioned? Dust-free? Away from running water?)

If new buildings or extensions are being constructed, different relevant departments and groups need to work closely together to design the rooms and plan the service supplies. Planners, users, architects, service engineers, and equipment engineers need to be consulted.

Site preparation can be carried out by:

- in-house staff (for example, the facility HTM team or a central/regional HTM team);

- maintenance staff from other national agencies (for example, electricians from the Ministry of Public Works);

- a contractor who has been hired (for example, a private company or an NGO partner); and

- the suppliers or their representative.

When planning and budgeting for the equipment, site-preparation costs should have been estimated for inclusion in the budget. However, as soon as the order is placed, the HTM working group / procurement unit should provide the supplier with details of the proposed equipment site and services, and officially request the necessary site preparation instructions.

Once these are received the HTM manager can plan the work, quantify the needs and costs for materials and contractors, and apply for a budget allocation. He or she should then oversee the work, and ensure it is undertaken before the equipment arrives.

Flowchart 8 below shows the common site preparation steps that may be required, depending on the type of equipment purchased. By the time the goods start to arrive, the site should be ready to receive them.

FLOWCHART 8: Common site preparation steps

An overview of the acceptance process

Each health facility should have an official acceptance process for equipment that arrives on site (a simpler process is used when equipment-related supplies arrive on their own). During the acceptance process, the following should be established:

the complete order has arrived;

- installation, commissioning, and initial training has taken place;

- the equipment is mechanically and electrically safe for users and patients and is functioning properly; and

- the equipment is entered into the health facility inventory.

A simple way to carry out these activities is to fill in a standard Acceptance Test Logsheet. This form is specially designed to make checking easier and to help to avoid mistakes. It is an important document since it is the first record to be placed in the equipment file and provides all relevant details of the start of the equipment’s life at the health facility, and commences the service history of the equipment. The Acceptance Test Logsheet has sections that cover all the components of the acceptance process, including:

- delivery/receipt of the equipment on site;

- unpacking and checking for damage and for the complete order;

- assembly;

- installation;

- commissioning and safety testing;

- official acceptance;

- initial training;

- registration – entering stocks into stores and onto records; and

- handover.

Each of these sections in the logsheet needs to be completed and signed off to indicate that the activity has been successfully completed. Once the logsheet has been fully completed, it is signed off to certify that the equipment and services are satisfactory. Only then should payment be made.

If there are problems with goods or services, the Acceptance Test Logsheet should not be signed; instead write a fault report on the equipment’s shortcomings should be logged, outlining the problems encountered and advising that payment be withheld until the problems have been addressed.

The equipment is not normally put into routine use until the complaints have been resolved, the logsheet finally signed off, and the payments made. The acceptance process is straightforward for common low-complexity items of equipment that are simple to use. Installation, commissioning, and initial training are not major activities and can happen all at once – e.g. for a mobile examination lamp:

- Installation involves using a test meter to check the electricity supply of the socket outlet, and then simply plugging in the lamp.

- Commissioning involves using a test meter to check the electrical safety of the lamp so that it will not give the operator an electric shock.

- Initial training involves ensuring the operator knows where the on/off switch is, how to handle the light bulb, and how to alter the angle of the head without pulling the lamp over.

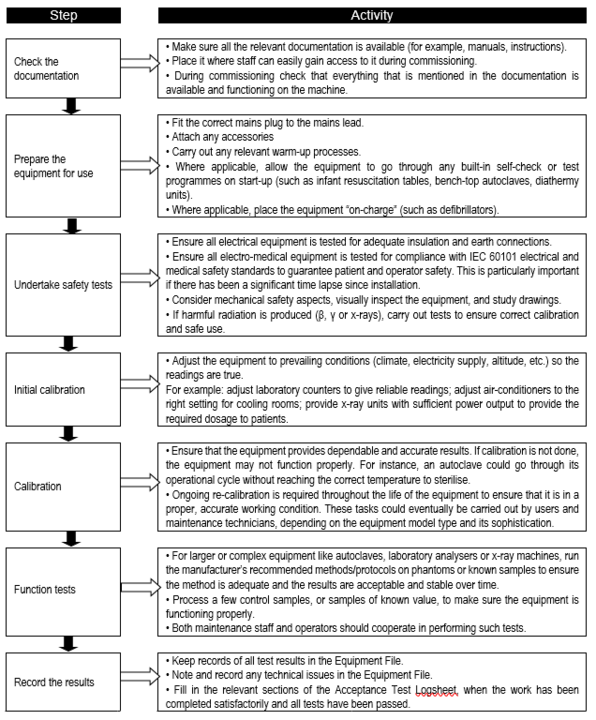

Commissioning

Commissioning usually, but not always, takes place straight after installation. The technical and safety aspects of the equipment should already have been specified and considered during the selection process. However, it is also essential to carry out performance and safety tests on each piece of equipment. Such tests validate that each piece of equipment is safe and is capable of performing its intended function. Performance and safety tests should be carried out regardless of whether equipment is purchased, donated, leased or borrowed by the health facility. The commissioning team and any visiting installers are responsible for ensuring these tests take place. The steps in the commissioning process are shown in Flowchart 9.

FLOWCHART 9: Key steps in the commissioning process

Once the equipment has passed its safety, calibration, and function tests, the commissioning team is in a position to:

- officially accept that the equipment has been received in a satisfactory condition, and

- officially accept the equipment as the institution/department’s property.

This could trigger the payment for the goods only. Payment for services can only occur when the training is finished, if it was part of the purchase contract. If the equipment has not passed the tests, negotiations would be commenced with the supplier and complaints procedures initiated. The equipment should not be accepted or used until these issues have been resolved. Once the equipment is accepted, staff can be trained in its operation and maintenance.

Registration and handover

Once equipment and supplies have been officially accepted, they can be registered in various health facility records and systems, process them, and stored or used as appropriate. The commissioning team is responsible for ensuring that all these activities take place.

Entering new equipment orders into health facility records

All equipment and equipment-related supplies need to be entered into the health facility’s records and systems. The most common records and systems are the:

- Equipment Inventory (manual or computerised). The HTM manager should enter new major pieces of equipment onto the Equipment Inventory. The type of information recorded should identify the particular piece of equipment, its manufacturer and location. The HTM manager can gather this information from the Acceptance Test Logsheet and the Register of New Stocks form. In addition, the HTM manager should allocate a unique inventory code number to each piece of equipment and ensure the equipment is labelled/marked with this code number.

- Equipment File (manual or computerised). This acts as a service history for a particular piece of equipment. The HTM manager should open a new Equipment File for each piece of equipment, and label the file with the equipment’s inventory code number. The type of information recorded in this file at the acceptance stage should include details of the manufacturer/supplier and purchase contract terms. Much of this information will be contained in the completed Acceptance Test Logsheet, which should be the first document placed in this file with supplementary data as required. Subsequent records placed in the Equipment File are of any maintenance work carried out so that the file becomes the equipment’s service history.

- Planned preventive maintenance (PPM) programme. The HTM manager should register equipment for any PPM carried out by maintenance staff (if it is taking place), and enter it onto their PPM timetable so that it gets attention at regular intervals. On handover of the equipment to the user, the HTM manager should liaise with the head of the user department about registering the equipment for any user PPM [BvR1] taking place, and entering it onto their user PPM timetable [see Section 10.2 for further discussion on maintenance].

- Equipment card. This is a piece of card or laminated sheet that is permanently kept with the equipment. It can provide users with a summary of the equipment care instructions and a summary service history, such as dates when routine inspections, testing, and servicing took place.

- Register of New Stocks form. This provides the Stores Controller with all the information required for entering each new piece of equipment and its supplies into the stores stock control system. The commissioning team should (partially) complete this form by gathering information from the available contract, packing lists, or invoice, according to a standard format. The type of information should identify the manufacturer/supplier’s order codes, description, and batch sizes of the equipment, consumables, accessories, and spare parts. The Stores Controller finishes completing the form by allocating and recording each item’s unique stores code. The Stores Controller provides copies of the finalised forms to the user departments and HTM team so they can order the correct replacement items in future. The HTM manager keeps this form in the relevant Equipment File.

- Registering warranties. The guarantee or warranty of the equipment (if applicable) needs to be registered. The date of commencement and the period of the warranty which have been agreed with the supplier must be entered into all relevant procurement, finance, and maintenance records.

- Note: Once the equipment has been checked and is confirmed as safe and ready for use, it is sensible to highlight this fact. Use a simple strip of tape placed across the main controls of the apparatus to clearly show that it has been tested. It is preferable to use printed warning notice tape, but other types could be used.

Storing manuals

Operator and service manuals should be supplied with the equipment, according to the purchase document. It is important to make sure that manuals are kept in a safe place, and are not lost by staff. It is also important to make them widely available for use among users and maintenance staff. This can be done by:

- Storing the original copies in a safe place, such as the clinical engineering workshop library, the main stores office, or the HTM service library.

- Making two photocopies of all operator manuals received, and giving one set to the head of the relevant user department, and the other to the HTM team or workshop responsible for the equipment’s maintenance.

- Making one photocopy of the service manuals received, and giving it to the HTM team or workshop responsible for the equipment’s maintenance.

- Asking for manuals or their content in other formats, such as CD-Rom, video, DVD.

- Scanning the printed documents into a computer to convert them into electronic copies, and making them easily available to maintenance staff at many locations.

- Recording in the Equipment File how the manuals were distributed. This helps with monitoring and updating the manuals in future.

Training

Introduction

After successful installation and commissioning, the users and maintainers need training on the type of equipment and the model purchased. This training can take place straight after commissioning, with the installation team acting as the trainers. However, the training team often involves different people, such as those with clinical or training skills. In this case, the training may take place sometime later when the training team has assembled.

Ideally, the initial training occurs straight after commissioning. After the training, the equipment can be handed over to the user department for regular use. However, if there is a delay before training can take place, one may have to consider whether to hand over the equipment before training staff. We recognise that there will be pressure to do this as all staff want to start using new equipment as soon as possible.

However, this should only be done if:

- the equipment is a type that has been used before;

- the staff are familiar with the equipment; and

- experienced staff members are in charge of its use, until the remaining staff can be trained.

Note: Anyone using or working on equipment without proper training or authority whose actions result in an accident is likely to be found negligent.

Depending on the complexity of the equipment and the staff’s previous experience of it, initial training can include:

- good practice when handling the equipment;

- basic “dos and don’ts”;

- how to operate the equipment (along with familiarisation with the symbols and markings on the machine);

- the correct application of the equipment;

- care, cleaning, and decontamination;

- safety procedures;

- planned preventive maintenance (PPM) for users; and

- PPM and repair for maintainers.

The level and nature of training provided depends on whether the equipment is:

- A standard make and model. If staff are familiar with the equipment, in-house staff could train new users and provide refresher training for other staff. The training sub-group should produce suitable and necessary training resources and handouts for the trainees, using the operator and service manuals, and any videos available.

- A new make or model. If the equipment is unfamiliar, training should be carried out by the supplier or their representative, or by a central training team with knowledge of the equipment. The training sub-group should observe the training session, obtain copies of any overheads or handouts used, and compile its own training pack for future training.

Sometimes in-depth training is given only to very few staff members who, at a later stage, will train the rest of the users. In this case, a training timetable is needed to ensure the ongoing training occurs.

Note:

- One should ensure that the chosen trainees turn up for the training sessions, and maintain records of the training that individual staff members have received.

- A library of the training resources developed should be established.

- The representatives of both the commissioning team and visiting training team should sign the Acceptance Test Logsheet, to avoid later disputes.

Correct application

Staff may feel confident about how to operate equipment, but it is imperative that they also know the correct “application” for the equipment. Staff need to be able to apply their taught (clinical) procedures correctly, and to employ the correct methods of application so that equipment is used to its fullest capacity.

Staff will need to be trained in order to fully appreciate when and how to use equipment. They will need to know:

- when different features will be employed for different patients or uses the range of assistance a machine can offer them;

- how to alter the relationship between the machine and the patient, or sample, for different purposes; and

- the different procedures to pursue for different disorders or treatments.

They will also need to understand the safety precautions they must take. Traditionally, colleges offering basic training for health are responsible for teaching clinical procedures. Thus, they must have access to the necessary equipment for this purpose, both in their teaching rooms and at suitable clinical locations such as hospitals.

It is important to note that training is an ongoing endeavour. Staff come and go, and even staff who have received initial training on an item of equipment may need refresher training. It is therefore useful to have a mechanism that will trigger training interventions. Flowchart 10 suggests appropriate triggers.

Flowchart 10: Example of prompts showing that training is required

When the device is removed from service, professional users should know how to clean it and to organise decontamination.

Special case: for home-based care or patient-operated devices

Professional users, clinical supervisors and prescribers need to make sure that training for end-users enables them to use a medical device/equipment safely and effectively, and to perform routine maintenance as appropriate for the medical device/equipment. For example, end-users of ambulatory infusion pumps should be aware of how the medical device works, including special features such as bolus delivery, and the risks of siphoning if a syringe is removed from a driver. It is also essential that end-users are provided with information contained in manufacturer’s instructions and that it is explained and, where necessary, expanded upon. Where possible, user organisations should provide the same standards of equipment and training for end-users as they do for staff.

Operation

Introduction

“Operation” of equipment means using the correct physical methods to get the equipment to work. In order to do this successfully, the user needs to know:

- the specific operating characteristics of the equipment;

- the operational procedures that make the machine work;

- how to use its various functions;

- how to make it perform its customary cycles and routines; and

- how to change the bulb, paper roll, batteries, etc.

The equipment manufacturer’s user manual is often the best source of this information. Other sources include:

- written resources from staff training sessions;

- experienced colleagues; and

- a wide range of reference material.

Box 12 provides some examples of general strategies when operating equipment

Box 12. General strategies when operating equipment (for users)

|

Each type of equipment has specific operating instructions. When operating equipment, it is also essential to follow good strategies for using consumable materials.

Equipment users should only operate equipment for which they are suitably qualified. Clinical meetings, committee meetings, departmental meetings, or specifically organised training sessions can all be used to provide application training (as appropriate).

For specialised devices e.g. autoclave, x-rays, the right type of personnel are required to operate these devices. Certification may be a requirement for some specialised devices. Regular monitoring has to be carried out for certain specialised devices (e.g. radiation safety monitoring for x-ray machines). User manuals should be provided for all devices to enable users to operate all devices safely and effectively, as well as for trouble-shooting for simple problems encountered with devices.

Care and cleaning

To maximise the life of equipment, it is necessary that equipment users and maintainers know how to look after the equipment and clean it. Users must care for and clean equipment regularly, to a given timetable. It is beneficial to do this because:

- it is easier to see faults (such as damaged suction pump tubing) when the equipment is clean;